SIGEP

Geological and Paleontological Sites of Brazil

- 033

ROCAS

ATOLL,

SOUTHWESTERN EQUATORIAL ATLANTIC, BRAZIL

Date:17/09/1999

Ruy Kenji Papa de Kikuchi

kikuchi@ufba.br

Departamento de Ciências

Exatas, Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana

BR-116, Km 3 s/n, Campus Universitário, Feira de Santana, Bahia, Brazil

CEP 44.031-460.

© Kikuchi,R.K.P. 1999.

Rocas Atoll, southwestern equatorial Atlantic, Brazil. In: Schobbenhaus,C.; Campos,D.A.; Queiroz,E.T.; Winge,M.; Berbert-Born,M. (Edit.) Sítios Geológicos e Paleontológicos do Brasil.

Available on line 17/09/1999 at the address http://www.unb.br/ig/sigep/sitio033/sitio033english.htm [Actually

https://sigep.eco.br/sitio033/sitio033english.htm]

[SEE

PRINTED CHAPTER IN PORTUGUESE] (The above bibliographic reference of author copy rights is required for any use of this article in any media, being forbidden the use for any commercial purpose)

|

ABSTRACT

Rocas is the first marine

protected area created in Brazil. It is a Biological Reserve and therefore the

only human activity allowed there is scientific research. It is an ellipsoid

atoll with an internal area of about 7.5 km2. Its largest axis (E-W)

is 3.7 km long, and the shortest (N-S) is 2.5 km long. An algal ridge limits the

reef flat, that is dominated by a coralline algae-vermetid gastropods

association growing as small linear ridges. In the reef front (in some grooves),

in the pools and in the lagoon, corals (Siderastrea

stellata, Montastrea cavernosa and

Porites sp) are found. Seismic

refraction profiles revealed the presence of two subsurface strata. A 11.6 m

long drill core on the western part of the reef, with the recovery rate of 40%,

shows that the Holocene sequence of Atol das Rocas was primarily built by

coralline algae and, subordinately, by corals, along with some encrusting

foraminifer Homotrema rubrum and

vermetid gastropods. The reef growth began before 4.8 ky BP with the accretion

rate varying from 1.5 to 3.2 m/ky. Subaerialy exposed old reef spits, elevated

above tidal range, and a beachrock cliff in one of the cays present in the atoll

are evidences of a equal to or higher than present sea level in Rocas, earlier

in the Holocene. Low degree of competition for space and low grazing pressure

may be the ecological reasons that promoted such a strong growth of coralline

algae in Rocas.

INTRODUCTION

Rocas is a geomorphologic site because it is the only atoll in Southwestern

Atlantic, and one of the smallest in the world. It was discovered in 1503 due to

the sink of Gonçalo Coelho sailboat (Rodrigues

1940)

. Thus, from this very first appearance in the nautical literature, its

low lying profile with only two cays and some rocks outcropping from sea had

always had the meaning of hazardous place.

Rocas

is a geologic site because as a reef it is a carbonate deposit that results from

the building activity response of benthic organisms to environmental parameters

such as light availability, hydrodynamics and relative sea level fluctuation.

Rocas

is a paleontological site because it was built dominantly by coralline algae,

and only secondarily by corals. This is an important fact because it is

generally accepted that coralline algae do not have potential to erect or to be

a primary builder of reefs in the Quaternary (Macintyre

1997)

.

At

last, but not least, Atol das Rocas is an ecological sanctuary because it is

home to a great number of migratory and resident sea birds, which rest, nest and

feed there. Among the most abundant birds in the atoll, there are the brown

tern, the brown and masked boobies and the frigate birds. Furthermore, like

Fernando de Noronha, it is a place of intense nesting activity of green turtles

and feeding activity for the hawksbill turtle. Around Atol das Rocas on the top

of the seamount platform there is a great quantity of commercial fishes.

Mollusks and crustaceans occur in great abundance, as well. Lobsters, as an

example, was one of the causes for the intense predatory fishing activity in the

atoll waters in the past.

The

purpose of this paper is to present an overview description of Atol das Rocas,

based mainly on Kikuchi (1994)

and Kikuchi & Leão (1997)

. Data on its composition and structure will be presented, showing that

the encrusting coralline algae were its primary reef builders. The reasons why

coralline algae predominate in such a conspicuous manner is discussed. I also

present evidences of a former sea level position in the Holocene equal to or

higher than the present sea level. This reinforces the general pattern of the

Brazilian coastal sea level curve that exhibits a transgressive period until

about 5.1 ky BP and a sea regression since that period. A brief comment on the

conservation status of the atoll close this chapter.

ENVIRONMENTAL

SETTING

The atoll is built on the western side of the flat top of a seamount within the

Fernando de Noronha Fracture Zone (Figure 1). It is located about 260 km east of

the city of Natal, in Northeastern Brazil, and 145 km west of the Fernando de

Noronha Archipelago (between 3°45’S and 3°56’S and 33°37’W and 33°56’W).

The lighthouse is located at 3

51’30”S and 33

49’29”W.

Figure

1: Location map of Atol das Rocas and the biological reserve limits

Kikuchi (1994)

shows, according to data obtained in Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas

Espaciais (INPE), that rainfall is irregularly distributed along the year, with

a monthly average of 860 mm, ranging from 183 mm (April/92) to 2663 mm

(August/92). In this same period, the air temperature ranged from 17.5°C

(April) to 35.8°C (February).

The

data of wind direction indicate that the dominant ESE winds occur along the

whole year, with an average frequency of 45% of the measured days. Between June

and August (southern hemisphere winter) SE winds occur in 35% of the days and

the frequency of E winds is 15% in the same period. Between December and April

(southern hemisphere summer) SE winds and E winds occur in about 20% of the days

with data available. Winds with speed varying between 6 and 10 m/s dominate

along the whole year, but during winter, winds with speed between 11 and 15 m/s

are common. Velocities higher than 20 m/s were registered, more frequently,

during summer.

Tides

are semi-diurnal, with a maximum range of 3.2 m.

The

drift that characterize Atol das Rocas region is the Southern Equatorial

Current, which is originated on the African coast, from the Benguela Current. It

flows to west at a velocity ranging from 30 cm/s to 60 cm/s (Richardson

& McKee 1984; Silveira et al.

1994)

.

According

to Hogben & Lumb (1967)

80% of the waves that were registered in the region where this study

site is included, come from E and 15% from NE. Their periods range from 4 s to 7

s and their heights, from 1 m to 2 m. Melo (1993)

, however, point out that during December and March this behavior can

change, with the occurrence of waves with 15 s to 18 s period and 2 m high waves

coming from the northern hemisphere.

Water

temperature in the outside of the atoll averages 27°C, with minimum value of

25.5°C and maximum value of 28°C. In the inner reef, water in the pools can

reach 39°C. Available data of salinity, indicate that it averages 37 salinity

units (su), varying from 35 su to 42 su. Some data on pH, measured during a

couple of days during the summer of 1991, in the inner part of the reef, show

values varying from 5 (at night) to 11 (at noon) (Kikuchi

1994)

.

Water

visibility during good weather conditions is greater than 20 m. A good

visibility is evidenced in the TM/LANDSAT image (Figure 2), where, in the blue

channel, it is possible to identify bottom features in depths up to 30 m.

Figure 2: A. TM/LANDSAT satellite image from Rocas atoll, blue band. The scale

bar (white) is 1 km long.

B: Geomorphology map of Atol das Rocas.

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

The existence of Atol das Rocas was first registered in the XVI Century

Cantino’s Map (Andrade

1959)

. The first detailed map of the atoll apeared in 1852, by Leutnant

Phillip Lee (Rodrigues

1940)

. In that time it was still named Rocas shoal (Baixo das Rocas) or Cabras

Shoal (Baixo das Cabras). It was in the bathymetric chart by Comander Vital de

Farias in 1858 that Rocas was first described as an atoll (Rodrigues

1940)

. Léry (1980)

was the first naturalist to give a brief and faint description the

atoll. It was only in Andrade (1959)

that Rocas received a deeper scientific description. Among other things

he described the morphology of the reef flat, the lagoon, of some pools, the old

reef spits and of the beachrock that occurs in Cemitério islet. These two

latter features were considered indications of a former higher relative sea

level in the atoll and correlated with evidences of higher sea level in the

Holocene found in the Brazilian coast in Pernambuco State (Andrade

1959)

. Thus, Holocene sea level fluctuations were considered of primary

importance on the build-up process of Rocas. Due to the low occurrence of corals

on the reef flat, Andrade (1959)

suggested that Rocas was entirely built by coralline algae (called by

the author as Lithothamnium).

The

controversy about the reef's composition and its classification as an atoll

began with the paper by Vallaux (1940)

. He points out that the reef is composed by coralline algae and that the

lagoon would not deserve this name because of its shallow depths. The issue was

founded on the dispute that occurred in that time between the theories about the

driving mechanism of reef evolution. Darwin's ideas about the 3 successive

stages of reef evolution in the Pacific, from fringing reefs to barrier reefs

and finally to atolls, all driven by isostasy was jeopardized by Daly who

proposed an alternative hypothesis. According to this author, eustatic sea level

changes were responsible for carbonate accretion and solution. Thus, high

frequency sea level rise and fall along geologic history were considered the

cause of reef evolution. The first hypothesis implied that carbonate accretion

on atolls would be thick, with deposits at least as old as the early Tertiary,

and the lagoons great depths were taken as evidences of this processes.

According to the second, the glacial-control theory, reefs in general (and

atolls in particular) would be a thin Pleistocene strata since reef substrate

would not have changed its position throughout reef development. Later in this

century, with the results of borings in the Pacific atolls it was proved that

Darwin's ideas were correct as a general model of reef evolution but, at the

same time, it was seen that the Quaternary thickness of reefs was generally thin

and that eustatic sea level change had an important role in reef development.

Thus, the residual blocks of reefs found on the eastern side of the atoll

surface and the beachrocks present on one of the atoll cays, that indicate a

higher sea-level in the Holocene, are not evidences that falsify the

classification of Rocas as an atoll, as pointed out by Andrade (1959)

in support to Vallaux's ideas. Based on its geomorphological aspects, it

will be shown that Rocas is a true atoll, despite its shallow (6 m deep) but,

nevertheless, navigable lagoon.

The

tectonic setting and substrate character of the atoll were considered by Almeida

(1955), who states that Rocas atoll and Fernando de Noronha Arquipelago belonged

to an alignment of seamounts, which is a branch of the meso-oceanic chain. Bryan

et al. (1973) shows evidences of the

continuity of this alignment through the continental margin in the Rio Grande do

Norte State and into the Brazilian coast and hinterland in the Ceará State.

Gorini (1981) confirms the morphology of this sea-mountains alignment and named

it as Fernando de Noronha Fracture Zone. According to the last author, this

fracture zone is a counterpart of the Jean Charcot Fracture Zone, in the eastern

margin of the South Atlantic Ocean. Cordani (1970) obtained ages in Fernando de

Noronha rocks spanning from 12 to 1,8 m. y. B.P. He adds, though, that the

volcanic activity of the Archipelago might have begun earlier, around 39 m. y.

B.P. Thus, sitting to the west of Fernando de Noronha, Rocas' sea-mount must

have begun to form earlier. Nevertheless the volcanic activity in the seamount

do not necessarily stopped much earlier.

Andrade

(1960) shows that the beachrock grain size is similar to that of the islets'

sediment. Coutinho & Morais (1970) study samples collected on the bottom

surface of Rocas and Fernando de Noronha and observe that it is “biogenic”

carbonate sand, composed mainly by coralline algae (Melobesioidae, Family

Coralinaceae), plates of the green calcareous algae Halimeda

and benthic foraminifers (mainly Amphistegina

radiata e Archaias sp). Tinoco (1972)

studies the foraminifers fauna of bottom surface sediments of Rocas and

found that Amphistegina radiata and Peneroplis

proteus dominates the sediment to

depths greater than 45 m but Archaias

angulatus is more abundant near the atoll and inside it.

SITE DESCRIPTION

Geomorphology

Atol das Rocas is a reef that developed on the flat top of a seamount (Figure

1), where depth ranges from 15 m to 30 m. It is an atoll with elliptical shape,

opened on its western and northern parts. Its greater axis, oriented E-W, is

about 3.7 km long and the minor axis, oriented N-S, is about 2.5 km long (Figure

2). Despite its small dimensions, the reef front, reef flat and a lagoon can be

clearly distinguished and subdivided into discrete features, such as reef front,

reef flat and lagoon (Figure 2A).

The

reef front has two distinct features: on the windward side (eastern and

southeastern side), it is an abrupt, nearly vertical wall, from the reef edge to

depths of about 10 m where a talus deposit occurs on its foot down to depths of

15 m. At this level, there is a flat surface colonized by fleshy and coralline

alga, corals and sponges, which extends up to 1 km to the east and south of the

atoll. In spite of the fact that this surface is colonized dominantly by green

and brown algae, with little or no sediment accumulation, colonies of Mussismilia

hispida and Millepora alcicornis,

together with sponges and rhodoliths are found on it. This is possibly the

surface of the substrate of Atol das Rocas. On the lee side a spur-and-groove

system develops from the reef edge to depths of 18 m.

The

reef flat is subdivided in two components: the reef proper and a sandy deposit

(Figure 2B). The reef proper (reef ring) is 100 to 800 m wide, interrupted

occasionally by pools and opened by two channels in the leeward side of the

atoll, one on the western side and another at the northern side. These two

channels divide the reef proper into the windward arch and the leeward arch.

In

the reef flat there are features like channels, pools and sand cays. The reef

proper or the reef ring is the outer reef flat and contour the sandy deposit and

the lagoon. The surface of the reef proper is composed of linear ridges of

encrusting coralline algae associated with vermetid gastropods, most of which

are approximately parallel to the reef edge (Figure 2B). Branching coralline

algae (Jania sp., Amphiroa sp.),

green and brown macroalgae also grow on these linear ridges. Residues of a

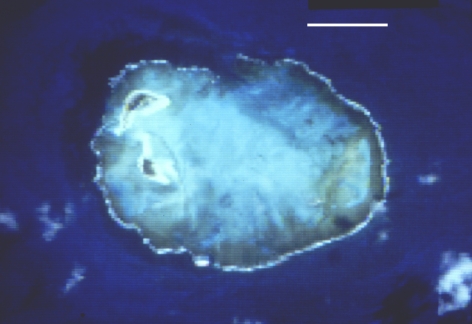

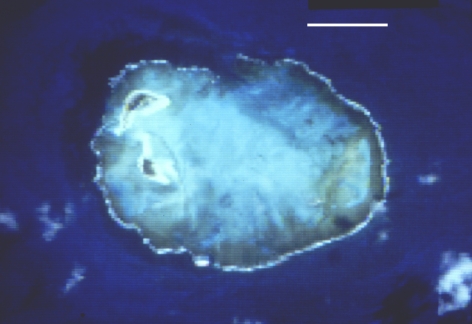

former higher reef building (Figure 3) appear at the windward arch of the atoll,

more frequently on the eastern part of the reef flat, but can be found also on

its southwestern part. This feature, named old reef spits or féo

in the literature (Battistini et al. 1975)

stands up 2 to 3 m above the surface of the reef flat, in Rocas (Figure

3). Notches on the spits feet (Figure 3) indicate that the mean high water

springs (MHWS) is about 0.5 m above the reef flat surface. They are composed

mainly of encrusting coralline algae. Vermetid gastropods and the foraminifer Homotrema

rubrum occur as subordinate components. The sandy deposit corresponds to a

greater part of what Andrade (1959)

calls as “very shallow lagoon”. It is composed mainly by a coralline

algae debris, medium to fine sand-grained. More than 50% of the fragments are

algal debris, with foraminifers tests and mollusk fragments appearing

subordinated (the mean frequency reaches about 10% each). In some places there

appear discontinuous and asymmetric ripples, produced by tidal flow on the reef

flat.

Figure

3: Photography of reef flat in the windward arch, E part of the atoll

On the edge of the windward arch there is a continuous algal ridge, about 20-30

m wide and nearly 0.5 m high. It is exposed above sea level during the low

tides. This is higher energy environment of the reef due to the fact that the

energy of the dominant wave train is dissipated on the reef edge. The algal

ridge is absent from the edge of the leeward arch, in the northwest side or

Farol cay.

A

shallow lagoon, with maximum depth of 6 m, is seen on the northeastern side of

the reef. It communicates with open sea through the northern channel (Figure 2),

called Barreta Grande. This channel is about 100 m wide and almost 100 m long.

Its depth varies from 6 m on its inner part to 10 m on its outer side. This

channel resembles a set of meandering small channels due to the growth of

several pinnacles in it (Figure 4). The corals Montastrea

cavernosa, Siderastrea stellata

and Porites sp grow on the walls of

the pinnacles. The bottom surface of the spaces between the pinnacles is

composed of gravelly sand sediment. The flow through this channel is tidally

controlled. The western channel on the other hand, is much smaller and short

(less than 50 m in each dimension). The flow through this channel is constantly

to outside of the atoll.

Figure

4: Passage between two pinnacles in Barreta Grande. Depth is about 6 m and

bottom surface is made of gravel

Several

pools occur on the reef proper (Figure 2B). They are 3 m deep at maximum, during

the low tides and can attain up to 400 m in length. This is the case of the

Turtle pool, on the eastern side of the atoll. The borders of the pools develop

overhangs and the coalescence of several individual pinnacles can also be seen

(Figure 5). This is an evidence of the process that originated the reef ring. In

the greater pools, isolated pinnacles can be seen as well. The bottom of the

pools are covered with sand.

Figure 5:

Pool on the south part of the atoll. Note the flat top of the pinnacles at water

surface level on the central part of the photo and the transition to the reef

flat.

There are

two sand cays on the western part of the atoll (Figure 2). The southern cay is

called Cemitério and has a cross bedded beachrock cliff 1.5 m high, on its

northeastern side. The height of this cay is about 2 m above the reef flat

level. A lighthouse was built on the northern cay called Farol. This cay is

about 3 m higher than the reef flat level and there is not beachrock developed

on it.

Rocas is

composed of zones frequently found in the Caribbean atolls despite its reduced

dimensions and formation of an semi-closed ring (Figure 2B, Table 1). This

latter characteristic is not a common feature found in the described atolls

(Stoddart 1965). However, comparing Rocas with other Atlantic atolls, many

similarities in the general morphology of the reef can be seen, as shown in

Table 1. Examples of this latter are the slope of the fore reef, that can be

compared to that found in Alacrán reef (Kornicker and Boyd 1962); the width of

the reef proper (ring), that is of the same order found in the Nicaraguan atolls

(Milliman 1969); and the thickness of the Holocene section and the physiographic

origin, that can be matched with that of Hogsty reef (Milliman 1967).

Table

1: Comparison of morphologic characteristics

between Rocas and the other Atlantic atolls

|

|

ROCAS

(Kikuchi

1994)

|

HOGSTY

(Milliman 1967)

|

ALACRÁN

(Kornicker &

Boyd 1962)

|

NICARAGUA

(Milliman 1969)

|

BELIZE

(Stoddart 1962)

|

|

Diameter (km)

|

2.5 x 3.7

|

5 x 9

|

11 x 22

|

3.5x8.5 to 16x32

|

7.5x35 to 16x49

|

|

Area (km2)

|

7.5

|

±40

|

259

|

25 to 260

|

203 to 530

|

|

Seamount top slope

|

0.2° to 0.15°

|

31° to 61°

|

0.02°

|

?

|

14° to 18°

|

|

Depth of lagoon (m)

|

0 to 6

|

6 to 8

|

15

|

10 to 20

|

6 to 43

|

|

Reef ring width

(km)

|

0.2 to 1

|

2

|

2.5

|

0.5

|

|

|

Holocene thickness

(m)

|

> 11.4

|

18

|

33.5

|

?

|

?

|

|

Continuity

|

closed

|

open leeward

|

open leeward

|

open leeward

|

open leeward

|

|

Physiografic

province

|

seamount

|

seamount

|

continental shelf

|

banks

|

platform banks

|

Reef structure and

composition

The results of the seismic survey, allowed the detection of 3 strata. Kikuchi (1997)

published a reevaluation of the data presented in Kikuchi (1994), in

which the mean velocities of each strata were the following:

v0

= 0.33m/ms

v1 = 2.50m/ms

v2 = 4.70m/ms

from the

shallower to the deeper strata.

Thus, the

layers thickness are:

z0

= 1.7m

z1 = 10.0m

were z0

and z1 summed up together are thickness of the Holocene section of

the reef. The bedrock (v2) upper limit depth in the investigated

site, thus, has a minimum value of 11.7m (Figure 6).

The upper two seismic layers of the reef sequence can be

identified as only one layer of Holocene reefrock, based on data from the core

(Figure 6). The low velocity that defined the upper seismic layer, could

represent the occurrence of a cap of reef with water and air in its pores,

resulting from the low level of the tide at the moment of the seismic registers.

The Holocene section of Rocas atoll was almost completely cored. The ages

yielded by coral skeletons confirmed the Holocene age for this section. The core

hole drilled to a depth of 11.69m, with a recovery rate of 40%. Encrusting

coralline algae was the most abundant organism found in the core samples,

forming more than 60% of the recovered rock. This prominent role of coralline

algae in the building up of reefs is a common feature of Brazilian reefs, such

as seen in Abrolhos and in the northern coast of Bahia. A similar characteristic

is observed in reefs of Bermudas (boilers), studied by Ginsburg (1973)

, and also in the reefs of Antilles, studied by Adey & Burke (1977)

. Coral skeletons appeared only subordinately. They were fragments or

small colonies of the species Siderastrea stellata, Favia

gravida, Mussismilia hispida, Agaricia

sp and Porites sp and made up about 10% of the rock. Vermetid gastropods

and the encrusting foraminifer Homotrema

rubrum are responsible, each of them, for about 6% of the core and occur

associated with the coralline algae.

Figure

6: Schematic W-E profile of Rocas atoll, with interpretation of seismic survey.

The core hole is represented on the profile, together with its schematic

composition. The ages of the coral skeletons from the core are also plotted

The

pre-Holocene substrate of Rocas can be compared to the volcanic rocks that

appear in the Fernando de Noronha Archipelago (ultramafic to intermediate

volcanic rocks, according to Almeida, 1955

). The seismic velocity that characterize this lower layer is of the same

order of those from the basalts described in the subsurface of Bikini atoll

(Dobrin et al. 1949; Raitt 1954), in

Kwajalein and Sylvania guyot (Raitt 1953) e no atol Eniwetak (Raitt 1957). This

basal section (Figure 6) may be Tertiary, considering the ages obtained in the

volcanic rocks of Fernando de Noronha Archipelago dated in Cordani (1970).

Reef accretion and sea

level position

The 14C ages obtained from the core are 4.86 ky BP at the depth of

11.2 m, 4.41 ky BP at the depth of 10.5 m, 3.06 ky BP at the depth of 7 m and

0.84 ky BP at the surface (Figure 6, Table 2), and they indicate that the 2.5

m/ms layer corresponds to a Holocene reef sequence. Consequently reef growth, at

the cored site, must have begun at about 5 ky BP and grew up to present sea

level with an average accretion rate of 2.8 m/ky (from 1.5 m/ky to 3.2 m/ky,

Table 3). The age of a skeleton of S.

stellata, of 2.02 ky BP, found in life position on one small old reef spit

on the southwestern part of the windward arch, 0.5 m above the level of the reef

flat surface, indicates that parts of the reef reached the present level of the

sea at about 2.0 ky BP. The dates yielded by the beachrock ranging from 1.91 ky

BP to 2.83 ky BP (Table 1), are concurrent with the age of the coral on the reef

spit, what reinforces the hypothesis that some parts of the reef have already

reached the present position of sea level between 3.0 ky BP and 2.0 ky BP.

Table

2: 14C ages of coral skeletons (Ss = Siderastrea

stellata, Fg = Favia gravida) and

mollusk shells (mol) from the reef surface, the core samples and the Cemitério

island beachrock.

|

Location

|

Material

|

Lab no.

|

Conventional 14C

age

(ky BP)

|

|

reef front, 10 m

deep, surface

|

Ss

|

Bah-1758

|

recent

|

|

reef flat, 0.5 m

above surface

|

Ss

|

Bah-1759

|

2.02 ± 0.16

|

|

reef flat surface

|

Ss

|

Bah-1803

|

0.94 ± 0.14

|

|

core top

|

Ss

|

Bah-1801

|

0.84 ± 0.14

|

|

core,

7.0 m deep, leeward ring

|

Ss

|

Bah-1806

|

3.06 ± 0.18

|

|

core, 10.5 m

deep, leeward ring

|

Ss

|

Bah-1807

|

4.41 ± 0.20

|

|

core, 11.2 m

deep, leeward ring

|

Ss

|

Bah-1808

|

4.86 ± 0.21

|

|

beachrock, 0.5 m

above reef flat

|

Fg

|

Bah-1800

|

2.63 ± 0.15

|

|

beachrock, 1.5 m

above reef flat

|

Ss

|

Bah-1796

|

1.91 ± 0.15

|

|

beachrock, 1.8 m

above reef flat

|

mol

|

Bah-1798

|

2.51 ± 0.17

|

|

beachrock, 2.0 m

above reef flat

|

Fg

|

Bah-1797

|

2.83 ± 0.16

|

The oldest 14C date obtained from the core (4.8 ky BP, Table 2) may

not represent the very beginning of reef development in Rocas. There may be a

difference in the reef age between the windward arch and the leeward arch, where

the core was bored. This difference is suggested by the following: i) the

continuos and well developed algal ridge on the windward arch, contrary to what

happens in the leeward arch, where the algal ridge is a feeble and discontinuous

feature; ii) the presence of reef residues (old reef spits) higher than

today’s sea level, on the windward arch (Figure 3); iii) the ages of the

skeletons collected on the reef flat, on the old reef spit and in the beachrock

indicate a possible difference of about 2.0 ky (Table 1) between the time when

the reef surfaced at the windward part and the time when it surfaced at the

leeward part. Considering that the reef accreted at the same average rate (2.8

m/ky, Table 3) in the two arches, reef growth should, thus,

have begun earlier on the windward arch, say at about 6.0 ky BP (Figure

6). It developed as an open atoll and the heights of the old reef spits indicate

that at 2.0 ky BP the reef should have reached up to 3 m above the today reef

flat surface (Table 1). The leeward arch began to develop at about 5.0 ky BP,

with an accretion rate increasing from 1.5 m/ky to 3.2 m/ky. Consequently, the

reef may have attained its semi-closed shape only recently, after the leeward

arch reached its present level, after 1.0 ky BP (Table 2).

Table

3: Reef growth rates, calculated from the ages of the coral skeletons obtained

in the core. Depth calculated with reference to reef flat level.

|

Interval

(m)

|

Rate

(mm/year)

|

|

0

- 7,0

|

3,2

|

|

7,0

- 10,5

|

2,4

|

|

10,5

- 11,2

|

1,5

|

|

average

|

2,8

|

Reef building flora and

fauna

The reef surface is mainly covered by soft algae and an association of living

coralline alga and vermetid gastropods. A study of the corallines by Gherardi (1999)

indicates the occurrence of the genera Porolithon,

Lithophyllum and Sporolithon,

and Lithoporella among encrusting

coralline algae. Massive corals, such as Siderastrea

stellata, Montastrea cavernosa and

Porites sp, only occur in protected

areas, mainly in the lagoon, within the pools and in some grooves of the reef

front. (Echeverría

et al. 1997)

published a list of cnidarians of Rocas in which, among the reef

building corals, Madracis decactis, Agaricia

agaricites, Porites astreoides, Porites branneri, Favia

gravida, and Mussismilia hispida

are cited, besides those species mentioned before. The almost absolute dominance

of Siderastrea stellata among the

hermatypic coral species is a striking characteristic of Rocas.

Two

aspects about the diversity of reef building organisms must be assessed. First

of all, it is the present dominance of coralline algae, which occurred along

whole development of the reef. Second, among reef building corals there is a

conspicuous dominance of a unique species, Siderastrea

stellata.

Although

it is presently recognized that coralline algae has a limited role in reef

building (Macintyre 1997)

due to ecological and environmental constraints and to their low

accretion rate (see Steneck 1986 and references wherin), a 11 m thick of reef

rock formed primarily by corallines accreted in a quite rapid average rate at

Rocas (2.8 m/ky). Figueiredo (1997)

shows that in Abrolhos also coralline algae growth is more elevated than

in reef environments elsewhere. Besides high hydrodynamic energy, low

inter-specific competition and a low degree of herbivory are conditions that

favor coralline algae development (Steneck

1997)

. It is possible that all these three conditions are met in Rocas. The

few number of coral species and the low cover rate of the reef surface by corals

that characterize Rocas, may result in a lower degree of competition for space

between corallines and corals than that found in other reef sites, and this may

have resulted in the enhancement of the coralline algae development. On the

other hand, although the biomass of grazers at Rocas seems to be equivalent to

the biomass of grazers in other reef sites in Brazil or in the Caribbean region

only one genera of coralline algae grazer parrot fish (Sparisoma)

is found at Rocas (Rosa

& Moura 1997)

. The fishes of the genera Sparisoma have weaker mouth muscles than those of the Scarus

genera, the commoner reef grazer, which are a more powerful coralline algae

grazer than Sparisoma. This difference in the composition of the fish fauna may

have contributed, also, to the enhancement of the coralline algae growth and

preservation since the grazing activity is one of the most important ecological

constraint to the development of coralline algae (Steneck 1986)

.

Considering

the dominance of Siderastrea stellata, Echeverría (1997)

suggest that the tolerance to environmental conditions such as high wave

energy and to high temperature variations may be the reason for the success of

this species in the atoll. The contribution of Geomorphology must be stressed,

as well. Due to the reduced dimensions of Rocas, water warmed during the low

tides (39°C to 40ºC), may influence the lagoon as well. The lagoon, besides

the pools is where corals can grow in profusion in the atoll.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Atol das Rocas is a biological reserve that belongs to the State of Rio Grande

do Norte. It is the first marine protected area established in Brazil, enforced

by Federal Act n° 83.549 of July 5th, 1978. In the National System

of Conservation Units (Sistema Nacional de Unidades de Conservação – SNUC),

biological reserve is a protected area category created for full conservation of

biodiversity. No recreational activity nor resources exploitation is admited

within these areas. However, visiting for scientific research and educational

purposes is allowed in special cases, with prior allowance of Brazilian

Institute of the Environment and of the Natural Renewable Resources (Instituto

Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Naturais Renováveis – IBAMA ).

The

Biological Reserve of Atol das Rocas includes not only the reef itself but all

seamount top limited by the 1000 m isobath. Its total area sums up to 360 km2.

Though it was created in 1978, it was not until 1990 that the conservation

activities began for real. The first reserve station camping was established

under the auspices of Marine Turtle Foundation (Fundação Pró-TAMAR) and of

Manatee Project (Projeto Peixe-Boi Marinho – IBAMA).

It

takes generally 26 hours to arrive the atoll, from the city of Natal (Rio Grande

do Norte). Research teams composed generally of 8 people shift every 25 days.

Each team is composed of 2 park rangers (from IBAMA) and 6 more people

(scientists, students and volunteers). Communication with the continent are made

with the use of SSB and VHF radio systems.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I

would like to thank the organizers of this book for the invitation and the

opportunity to write about a beloved object. Also, I’d like to thank Prof. Dr.

Zelinda M. A. N. Leão for opening the doors for me to the study of the

carbonate environment. Mr. Gilberto Sales, former chief, and Ms. Zélia Brito,

present Chief of Reserva Biológica do Atol das Rocas gave me the opportunity of

developing the fieldwork and helped during the field work in Rocas. The

TM/LANDSAT image was acquired in Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais

(INPE).

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

Adey, W.; Burke, R.B.

1977. Holocene bioherms of Lesser Antilles - Geologic control of development.

In: S.H. Frost; WEISS, M.P.; SAUNDERS, J.B. eds.

Reefs and related carbonates -

Ecology and Sedimentology.Tulsa, American Association of Petroleum

Geologists. p. 67-81.

Almeida, F.F.M. 1955. Geologia

e Petrologia do Arquipélago de Fernando de Noronha. Rio de Janeiro,

DNPM/DGM. 181 p.

Andrade, G.O. 1959. O

recife anular das Rocas (Um registro das recentes variações eustáticas no Atlântico

equatorial). Anais da Associação dos Geógrafos

Brasileiros, XI: 29-61.

Battistini, R.,

et al. 1975. Éléments de terminologie récifale Indopacifique. Téthys,

7: 1-111.

Bryan, G.M.; Kumar, N.;

Castro, P.J.M. 1973. The north Brazilian ridge and the extension of equatorial

fracture zones into the continent. In:

CONGRESSO BRASILEIRO DE GEOLOGIA, XXVI, Belém, Anais...,

SBG-Norte, p. 133-144.

Cordani, U.G. 1970. Idade

do vulcanismo do Atlântico Sul. Boletim

do Instituto de Geciências e Astronomia - USP, 1: 9-76.

Coutinho, P.N.; Morais,

J.O. 1970. Distribución de los sedimentos en la plataforma continental

norte-nordeste del Brasil. In: SYMPOSIUM ON INVENTORY OF RESOURCES OF THE

CARIBBEAN SEA AND ADJOINING REGION. Curaçao, 1970. Proceedings...,

p. 273-284.

Dobrin, M.B.; Perkins Jr,

B.; Snavely, B.L. 1949. Subsurface constitution of Bikini Atoll as indicated by

a seismic refraction survey. Bulletin of

the Geological Society of America, 60:807-828.

Echeverría, C.A.; Pires,

D.O.; Medeiros, M.S.; Castro, C.B. 1997. Cnidarians of the Atol das Rocas. In: INT. CORAL REEF SYM, 8th, Panama, 1996. Proceedings... ISRS. V. 1, p. 443-446.

Figueiredo, M.A.O. 1997.

Colonization and growth of crustose coralline algae in Abrolhos, Brazil. In: INT. CORAL REEF SYM, 8th, Panama, 1996. Proceedings... V. 1, p. 689-694.

Gherardi, D.F.M.; Bosence,

D.W.J. 1999. Modeling of the ecological succession of encrusting organisms in

recent coralline-algal frameworks from Atol das Rocas, Brazil. Palaios,

14: 145-158.

Ginsburg, R.N.; Schroeder,

J.H. 1973. Growth and submarine fossilization of algal cup reefs, Bermuda. Sedimentology, 20: 575-614.

Gorini, M.A. 1981. The

tectonic fabric of the Equatorial Atlantic and adjoining continental margins:

Gulf of Guinea to Northeastern Brazil. In: Asmus, H.E. ed.

Estruturas e tectonismo da margem

continental brasileira e suas implicações nos processos sedimentares e na

avaliação do potencial de recursos minerais.Rio de Janeiro, PETROBRÁS,

CENPES, DINTEP. p. 11-116.

Hogben, N.; Lumb, F.E.

1967. Ocean wave statistics. London, National Physical Lab., Ministry of

Technology. 263 p.

Kikuchi, R.K.P. 1994.

Geomorfologia, Estratigrafia e Sedimentologia do Atol das Rocas

(Rebio-IBAMA/RN). Salvador, 144 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado, Pós-Graduação

em Geologia, Universidade Federal da Bahia).

Kikuchi, R.K.P.; Leão,

Z.M.A.N. 1997. Rocas (Southwestern Equatorial Atlantic, Brazil): an atoll built

primarily by coralline algae. In: INT.

CORAL REEF SYM, 8th, Panama, 1996. Proceedings...

V. 1, p. 731-736.

Kornicker, L.; Boyd, D.W.

1962. Shallow-water geology and environments of Alacran Reef Complex, Campeche

Bank, Mexico. Bulletin of the American

Association of Petroleum Geologists, 46: 640-673.

Léry, J.d. 1980. Viagem

à terra do Brasil. São Paulo, Editora Itatiaia/Ed. Universidade de São

Paulo. 303 p.

Macintyre, I.G. 1997.

Reevaluating the role of crustose coralline algae in the construction of coral

reefs. In: Proc 8th Int Coral Reef Sym. Panamá, 1996, ISRS. V. 1, p.

725-730.

Melo, F., Eloi; Alves,

J.H.G.M. 1993. Nota sobre a chegada de ondulações longínquas à costa

brasileira. In: Simpósio Brasileiro de Recursos Hídricos, X, Gramado, 1993. Anais...,

ABRH, p. 362-369.

Milliman, J.D. 1967. The

Geomorphology and history of Hogsty Reef, a Bahamian atoll. Bulletin

of Marine Science, 17: 519-543.

Milliman, J.D. 1969. Four

southwestern Caribbean atolls: Courtown Cays, Albuquerque Cays, Roncador Bank

and Serrana Bank. Atoll

Research Bulletin, 129:1-26.

Raitt, R.W. 1954.

Seismic-refraction studies of Bikini and Kwajalein atolls. Bikini and nearby

atolls. Part 3. Geophysics. US Geological

Survey Professional Paper, 260S: 507-527.

Raitt, R.W. 1957.

Seismic-refraction of Eniwetak atoll. Bikini and nearby atolls. Part 3.

Geophysics. US Geological Survey Professional Paper, 260S: 685-698.

Richardson, P.L.; McKee,

T.K. 1984. Average Seasonal-Variation of the Atlantic Equatorial Currents From

Historical Ship Drifts. Journal of

Physical Oceanography, 14: 1226-1238.

Rodrigues, O.A.A. 1940. O

Atol da Rocas. Revista Marítma Brasileira,

LIX: 1181-1228.

Rosa, R.S.; Moura, R.L.

1997. Visual assessment of reef fish community structure in Atol das Rocas

Biological Reserve, off northeastern Brazil. In:

INT. CORAL REEF SYM, 8th, Panama, 1996. Proceedings...

V. 1, p. 983-986.

Silveira, I.C.A.; Miranda,

L.B.; Brown, W.S. 1994. On the origins of the North Brazil Current. Journal

of Geophysical Research, 99: 22501-22512.

Steneck, R.S. 1986. The

ecology of coralline algal crusts: Convergent Patterns and Adaptive Strategies. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 17: 273-303.

Steneck, R.S. 1997.

Crustose corallines, other algal fuctional groups, herbivores and sediments:

complex interactions along reef productivity gradients. In:

INT. CORAL REEF SYM, 8th, Panama, 1996. Proceedings...

V. 1, p. 695-700.

Stoddart, D.R. 1965. The

shape of atolls. Marine Geology, 3:

369-383.

Tinoco, I.M. 1972. Foraminíferos

dos bancos da costa nordestina, Atol das Rocas e Arquipélago de Fernando de

Noronha. Trabalhos do Instituto Oceanográfico

da Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, 13: 49-60.

Vallaux, C. 1940. La

formation atollienne de Rocas (Brésil). Bulletin

de L'Institut Océanographique, 37: 1-8.